When the lights fade and Sunshine begins, we see a girl suspended in midair, a gymnast who is graceful and determined, the embodiment of youth in motion. Beneath her leaps and landings lies another heartbeat, one she never expected to carry. Antoinette Jadaone’s Sunshine is not just a coming-of-age film. It is a confrontation with the silences that surround young women’s bodies, dreams, and choices in a country that too often fails them.

Sunshine’s journey unfolds in two voices, her own and that of the child inside her. Through Jadaone’s poetic direction, this imagined presence becomes more than a symbol. It is the echo of her innocence, the small and silent witness to her unraveling. As Cinema Escapist notes, the “imaginary friend” motif offers a haunting mirror, sometimes a companion, sometimes a burden, sometimes the whisper of a future she is too young to imagine.

From within her, the child feels the tremors of her mother’s fear, the racing pulse after every practice, the quiet sobs in dark corners. If she is still a child, how can she bear one? the film seems to ask. Through that inner voice, the audience is forced to see the cruel contradiction: the same nation that cheers Sunshine’s triumphs abandons her in her most fragile moment.

In the ABS-CBN review, critics note that Sunshine “is fantastic for a country that fails its women,” a biting truth beneath the praise. The film does not indict through speeches or slogans. It simply watches as systems collapse around a teenage girl who dares to need help.

No safe healthcare, no real sex education, no legal options, no forgiveness.

As Cinema Escapist observes, Jadaone transforms these absences into atmosphere. The silence of hospitals, the whispers in classrooms, and the judgmental gazes of adults all become a chorus louder than any dialogue. Sunshine’s body becomes a battlefield. Inside her, the unborn child is caught in the crossfire of faith, law, and moral rigidity.

In one of the film’s most haunting sequences, Sunshine speaks to her “imaginary friend,” a childlike voice that answers back. It is ambiguous whether this is the voice of the baby or of her own inner child, but it speaks truths adults refuse to hear: “I didn’t choose to be here. Neither did you. But we are here now, together.”

That moment crystallizes what Sunshine dares to articulate, that motherhood, forced or chosen, is not a moral question but a human one. The unborn child, imagined as both presence and conscience, does not demand to be saved. It demands that the world see its mother as someone worth saving too.

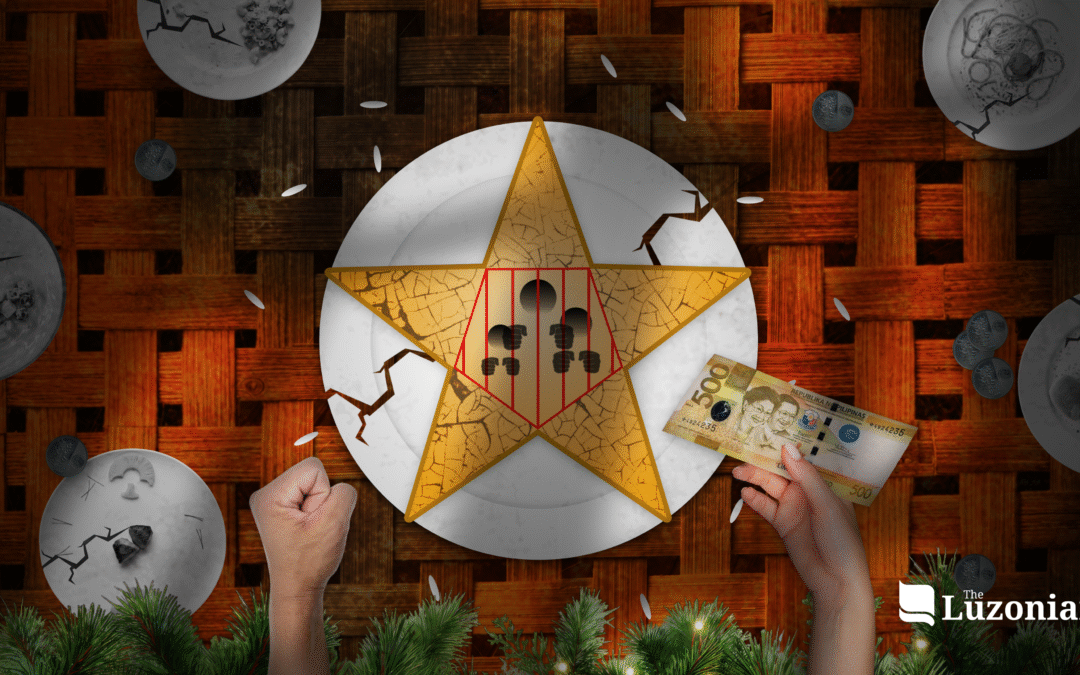

The Philippines, with its deeply Catholic roots and strict abortion laws, becomes more than just a setting. It is the unseen antagonist. Sunshine is framed by the tension between love and law, between tradition and empathy. The film shows that in a society where motherhood is glorified but mothers are unsupported, compassion becomes radical.

The dual perspective of the girl and the child allows audiences to feel the full weight of that contradiction. We hear the child’s hope and confusion, echoing in scenes where Sunshine trains alone, hides her swelling belly, or stares at her reflection after a competition. Each medal glitters less brightly, and each applause fades faster.

Maris Racal delivers a performance that feels like both confession and rebellion. She embodies the fragility of youth and the exhaustion of survival. Her eyes shift from the confidence of a champion to the quiet panic of a child who has run out of places to hide. Critics from Cinema Escapist praised her portrayal as “unflinchingly humane, a reflection of a generation failed by silence.” Through her, the imagined child becomes more than metaphor. It becomes memory, echo, inheritance.

In a time when reproductive health remains a taboo topic, Sunshine is not merely art. It is testimony. It asks hard questions in soft tones, demanding that audiences listen to what has long been buried beneath shame and doctrine.

It is a film about two lives, one already judged and one not yet born, both deserving of care. The child’s voice, though imagined, speaks for every silenced girl, every unseen mother, every unspoken grief.

“If she can love me, even when the world won’t, then maybe there is still light left in us.”

That is the quiet brilliance of Sunshine. It refuses despair. It finds, in the darkest corners, the faint but persistent glow of empathy, fragile, flickering, but never extinguished.