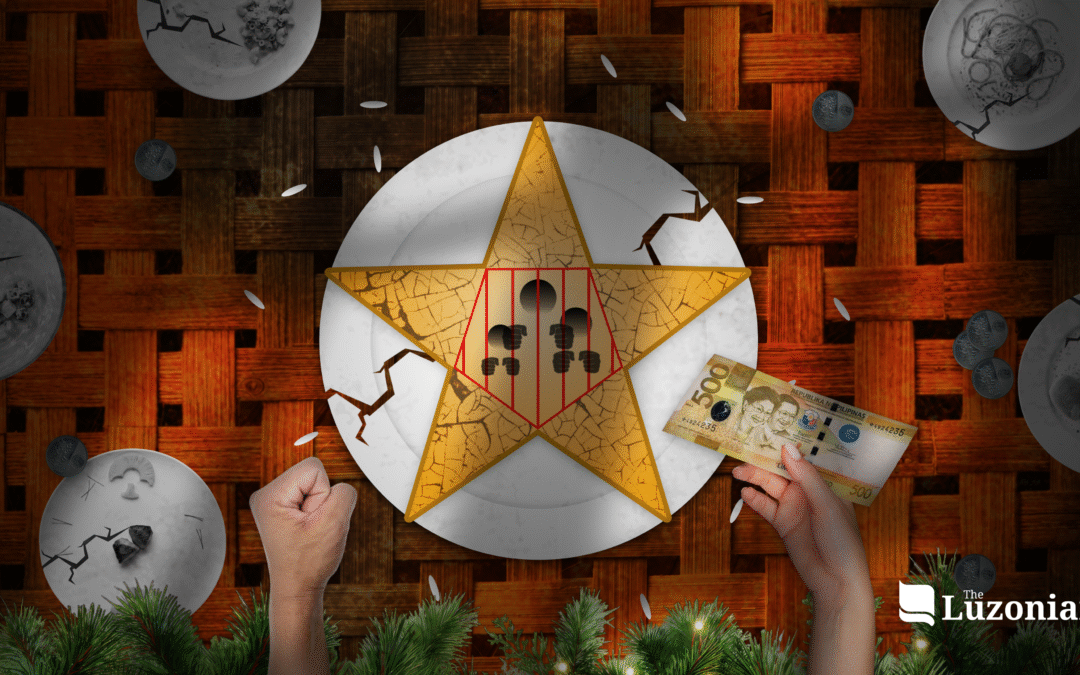

In many Filipino homes, a mother’s warmth is the light that embraces, while a father’s strength forms the walls that protect. But what happens when those walls harden into fists, and that light begins to flicker? Beneath the cold floors, something crawls in the house of Juan Tamban—drawn to silence, feeding on fear.

Written by Malou Jacob and directed by Tok Guerra, Juan Tamban was staged at the AEC Little Theater in May 2025. It revolves around the case of a 12-year old kid, Juan, who has fallen victim to illnesses such as malaria, amoebiasis, and epilepsy because of eating cockroaches, lizards, and rats—an interesting case for Marina who conducted a case analysis of Juan for her master’s thesis. However, beyond his physical illness, Marina unveils a far deeper wound that cripples Juan more than any other disease.

Juan lives in a cramped, makeshift home in an illegal settlers’ area, where the kitchen, bedroom, and dining space are all within arm’s reach—a space too small for comfort, yet large enough to foster violence. The walls often tremble, not because of decaying materials, but because of his father shouting profanities. Justino, a garbage collector with a past of drug abuse and a present consumed by gambling, embodies the worst of toxic masculinity. He shouts, insults, and lashes out—especially towards Juan and his mother.

His struggles, however, are not merely personal flaws. They mirror the broader societal systems that entrap many Filipino men in cycles of poverty, addiction, and despair. In one scene, Justino asks, “Kung parehong tao ang mayaman at mahirap, bakit kapag ninanakawan ng mayayaman ang mahirap, okay lang? Pero kapag mahirap ang gumawa, krimen?”

This line pierces through the heart of systemic inequality. The limited economic opportunities and the burden of fulfilling the traditional role of provider trap men like Justino in a vicious loop—one where survival often means breaking the law, and failure becomes a measure of masculinity.

Crushed by unrelenting societal and economic pressure, some men turn to dangerous escapes like drugs, gambling, and other vices. What begins as thrill or curiosity gradually spirals into a cycle of dependency and destruction.

Fathers pawn off appliances in hopes of a “winning bet.” Mothers endure insults and aggression masked by intoxication. Children are left trembling in dark corners, afraid of the next outburst. In the grip of addiction, homes that once promised safety become battlegrounds of fear.

Justino’s version of masculinity becomes something he passes on like a curse. In one scene, he berates his wife for “babying” Juan, claiming that he is becoming “too soft.” He compares him to his older brother Jaime, recently out of jail but considered “respected” in the neighborhood. This shows how toxic masculinity equates manhood with dominance instead of empathy. It reinforces a cycle where toughness is mistaken for worth, and softness is seen as weakness.

Yet the play digs deeper, exposing even more silenced forms of abuse. It also confronts one of the most silenced issues in Filipino society—the reality of marital rape, masked euphemistically in a scene where Justino demands for a “massage” from his wife.

Feminist theory shows this as part of patriarchal power structures that deny women bodily autonomy, even within marriage. Such normalization of denial of consent perpetuates misogyny, treating women as possessions rather than individuals with rights.

Disturbingly, such views persist even within the halls of power. During a Senate hearing on marital rape, Senator Robin Padilla sparked controversy when he asked, “Paano kaming mga lalaki na naniniwala sa sexual rights kapag kami ay in heat?” Citing Islamic teachings, he added, “Most scholars say that it is obligatory on women alike [to] not to refuse their husbands if they call them.” This rhetoric lays bare how deeply entrenched patriarchy remains—spanning class, religion, and institutions of authority.

While Juan and his mother are the most visible victims in the play, Marina—despite the comfort of her middle-class life—faces a more insidious form of abuse.

Her fiancé, Mike, never raises a hand, but he weaponizes guilt and emotional manipulation. Feeling “neglected” by Marina’s academic commitments, he pressures her to choose between love and ambition. His frustration eventually boils over into verbal aggression: “Wag mo akong sermonan na akala mo kung sino ka!”

This is violence too. Not the kind that bruises, but the kind that leaves lasting emotional wounds.

The Anti-Violence Against Women and their Children Act (RA 9262) enacted in 2004, defines such violence not only as physical harm but also includes emotional, psychological, and economic abuse. It encompasses threats, manipulation, and intimidation—any act that compels a woman or child to obey out of fear.

In 2023, the Philippine National Police recorded 8,055 cases under RA 9262, a 3.76% increase from the previous year. Yet this figure likely underestimates the true extent of abuse, as many women remain silent due to deep emotional barriers—shame, fear, and attachment to their partners—combined with hope that the abuse will end, all of which often prevent them from seeking help or leaving abusive relationships.

Juan Tamban reminds us that abuse wears many masks. Some are fists. Others are words that wound. Some enter through the front door as lovers, only to later reveal themselves as oppressors. Some kill slowly, like hunger. Some in an instant, like rage.

By shedding light on these layered violences, Juan Tamban does more than present a scene on stage—it opens the doors and exposes what crawls within: the rot of abuse, the vermin of misogyny, the pests of addiction and neglect. These are not mere metaphors, but real forces creeping through the cracks of countless Filipino households—infestations we must confront and eradicate.